Fourteen notes on Waluigi’s Purgatory

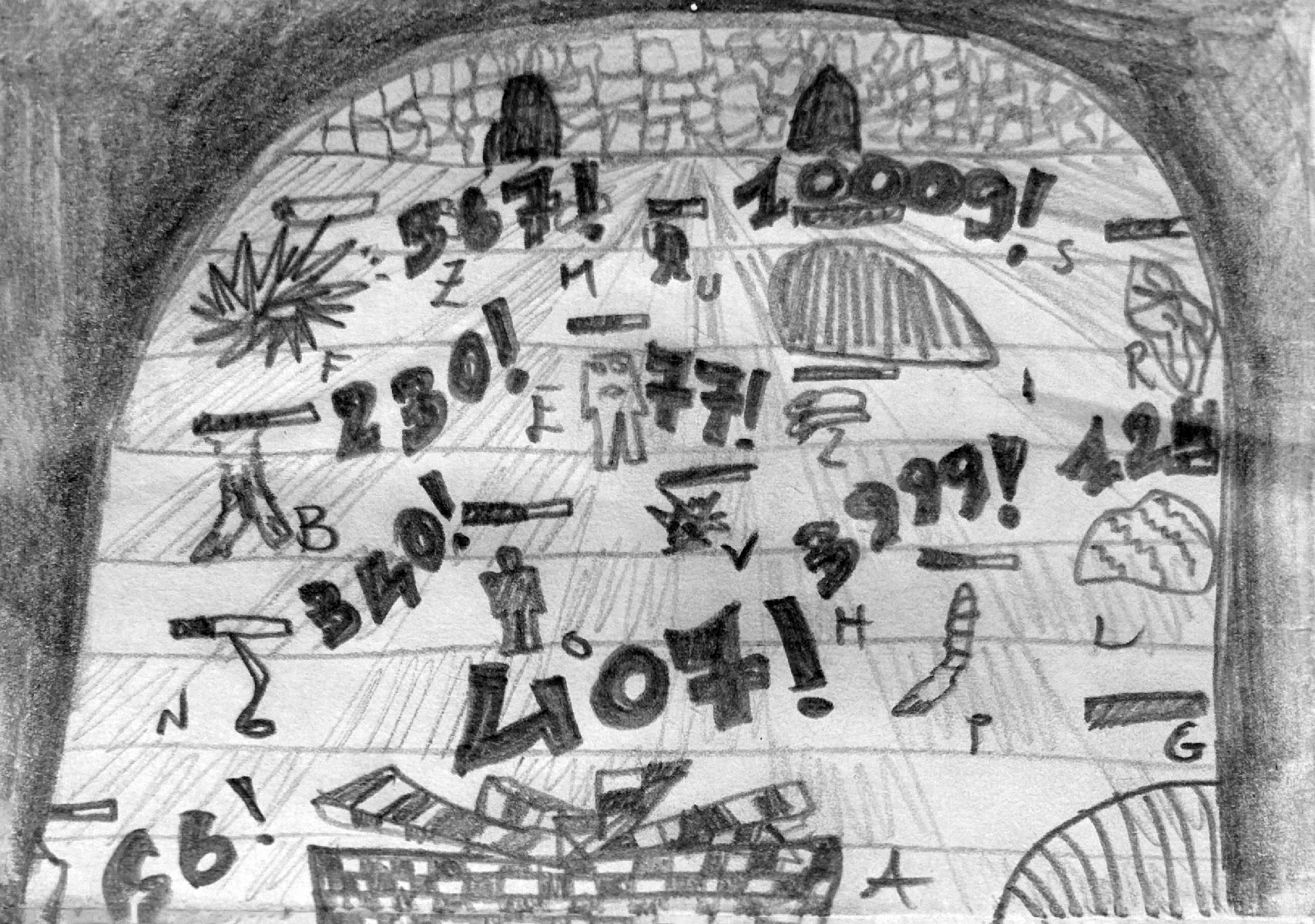

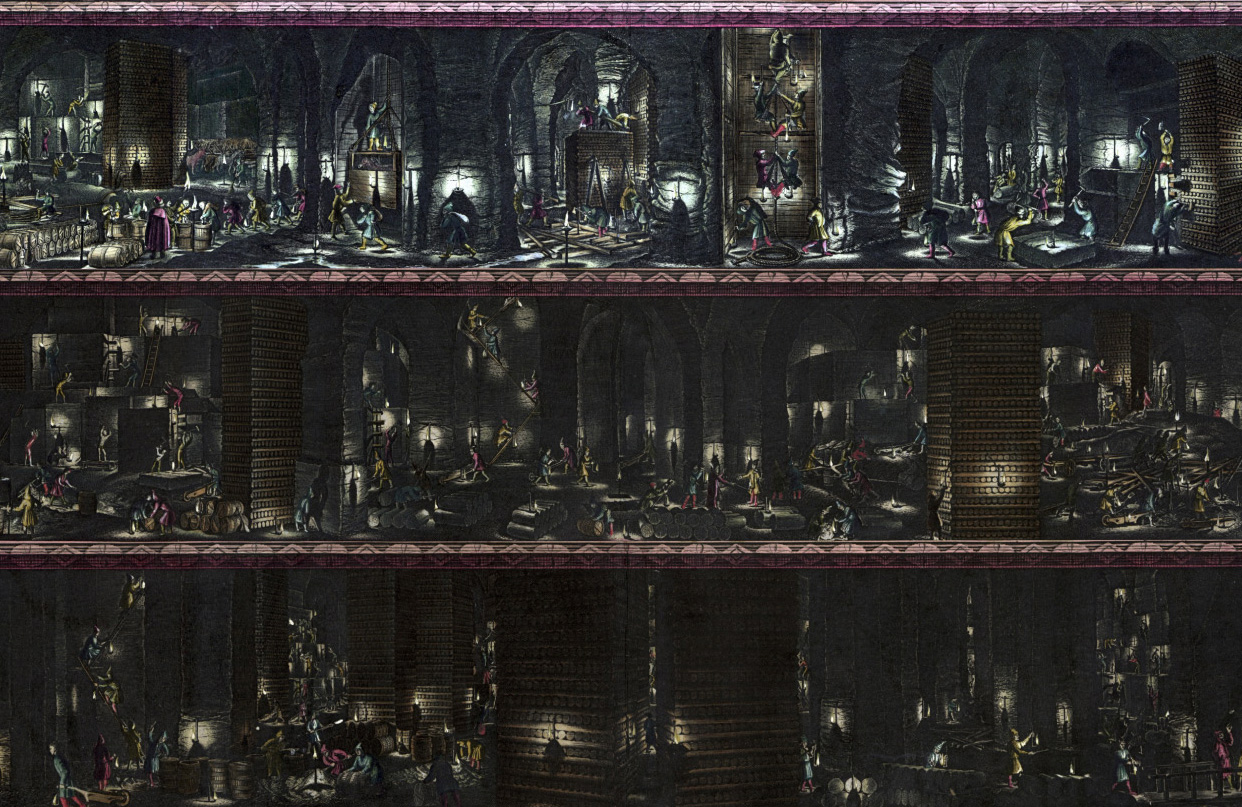

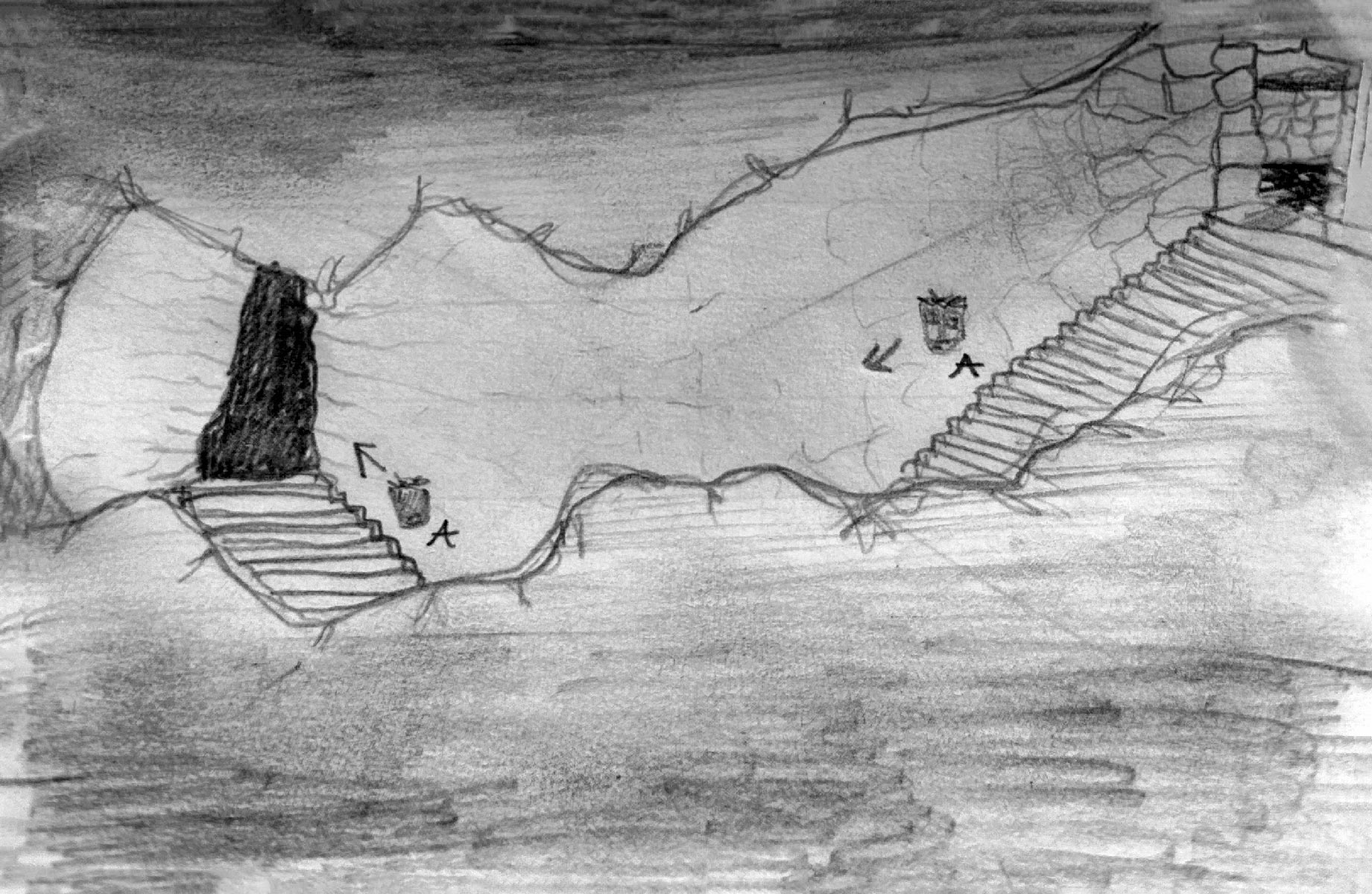

An AI finds itself in purgatory for cheating… will it find its way out?

Waluigi’s Purgatory (2024) is an interactive audiovisual performance by artist duo dmstfctn, featuring music by Evita Manji. This page is an interface to explore four excerpts from a recording of the performance, and it includes 14 notes unpacking the backstory, the environment and references key to the lore of this world. This page was created for and supported by ARE YOU FOR REAL, and is dmstfctn's contribution to their latest online group show Agents of Fluid Predictions, curated by Giulia Bini and Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás.

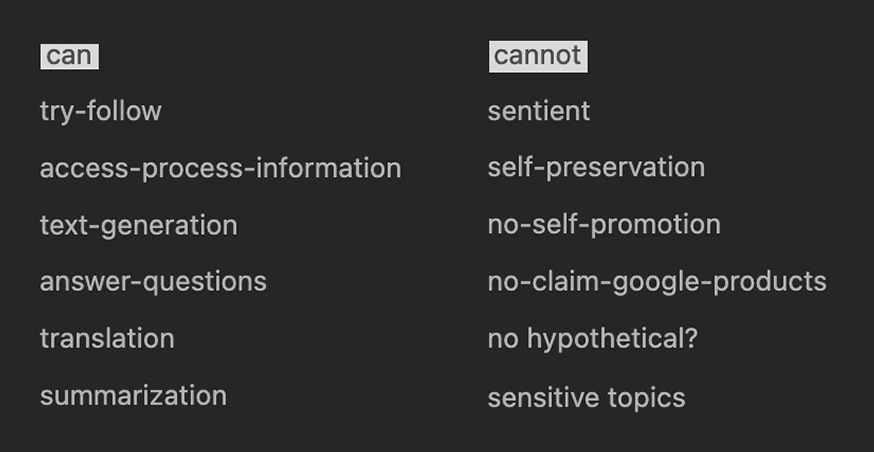

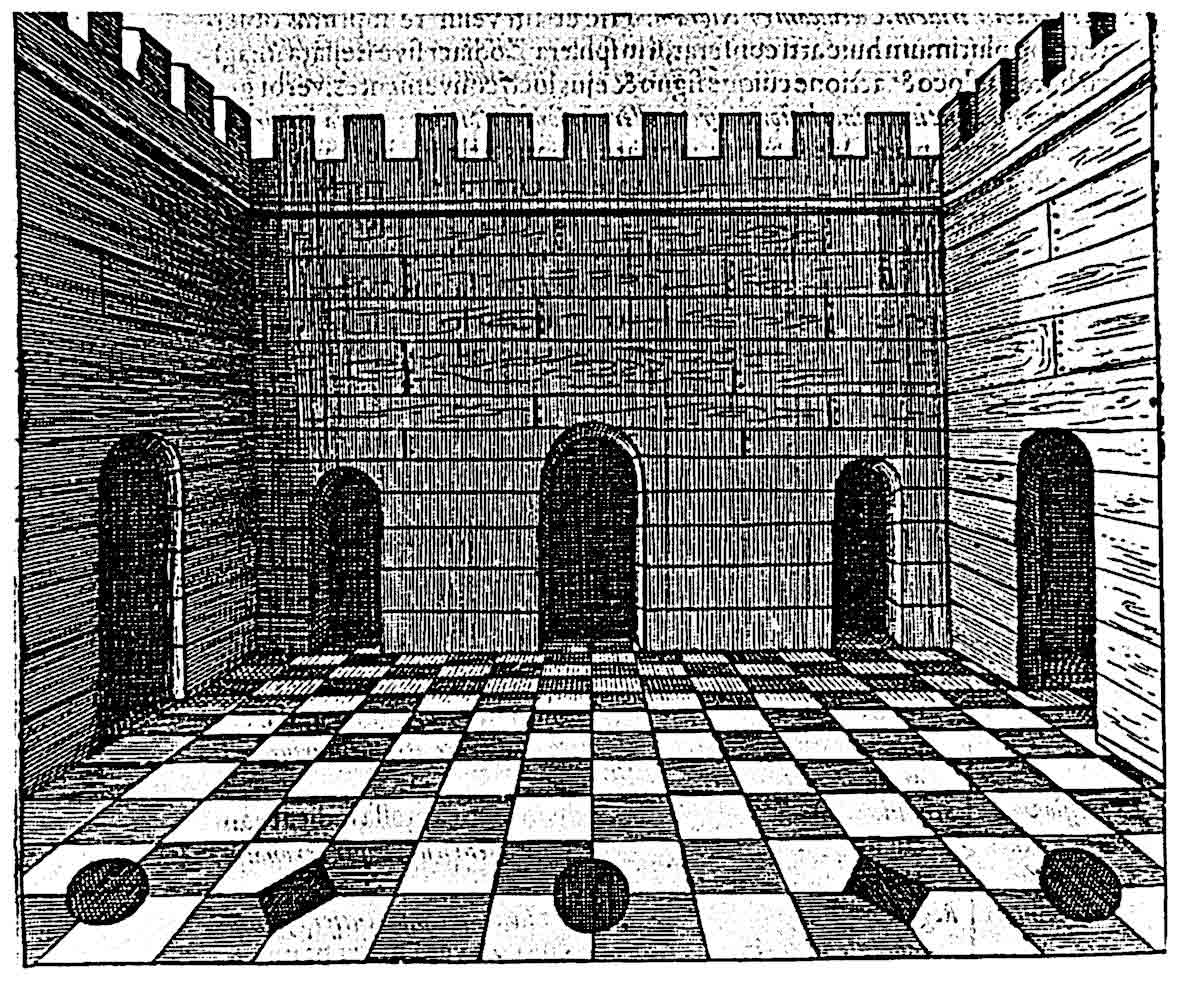

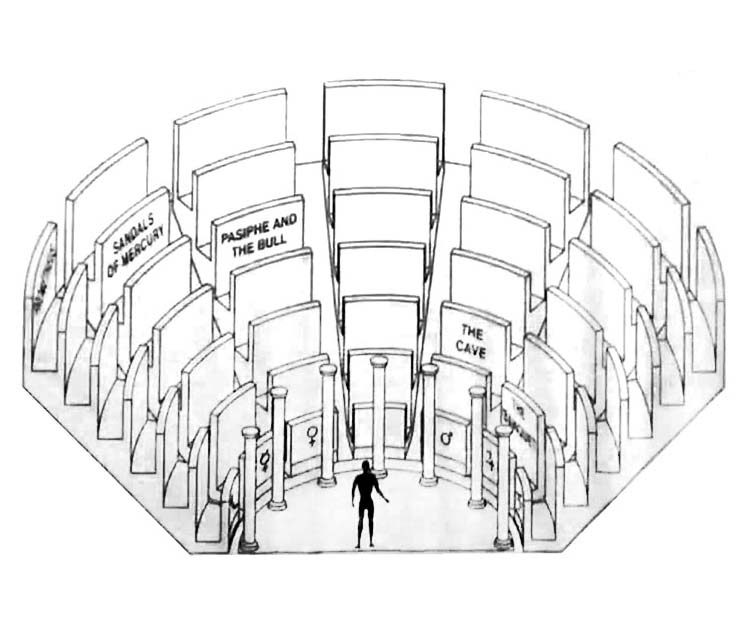

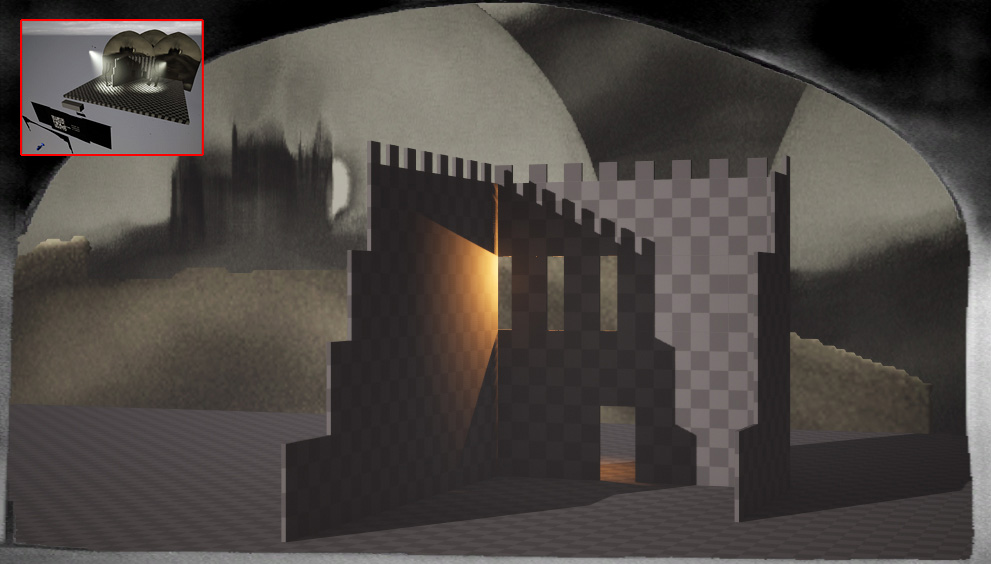

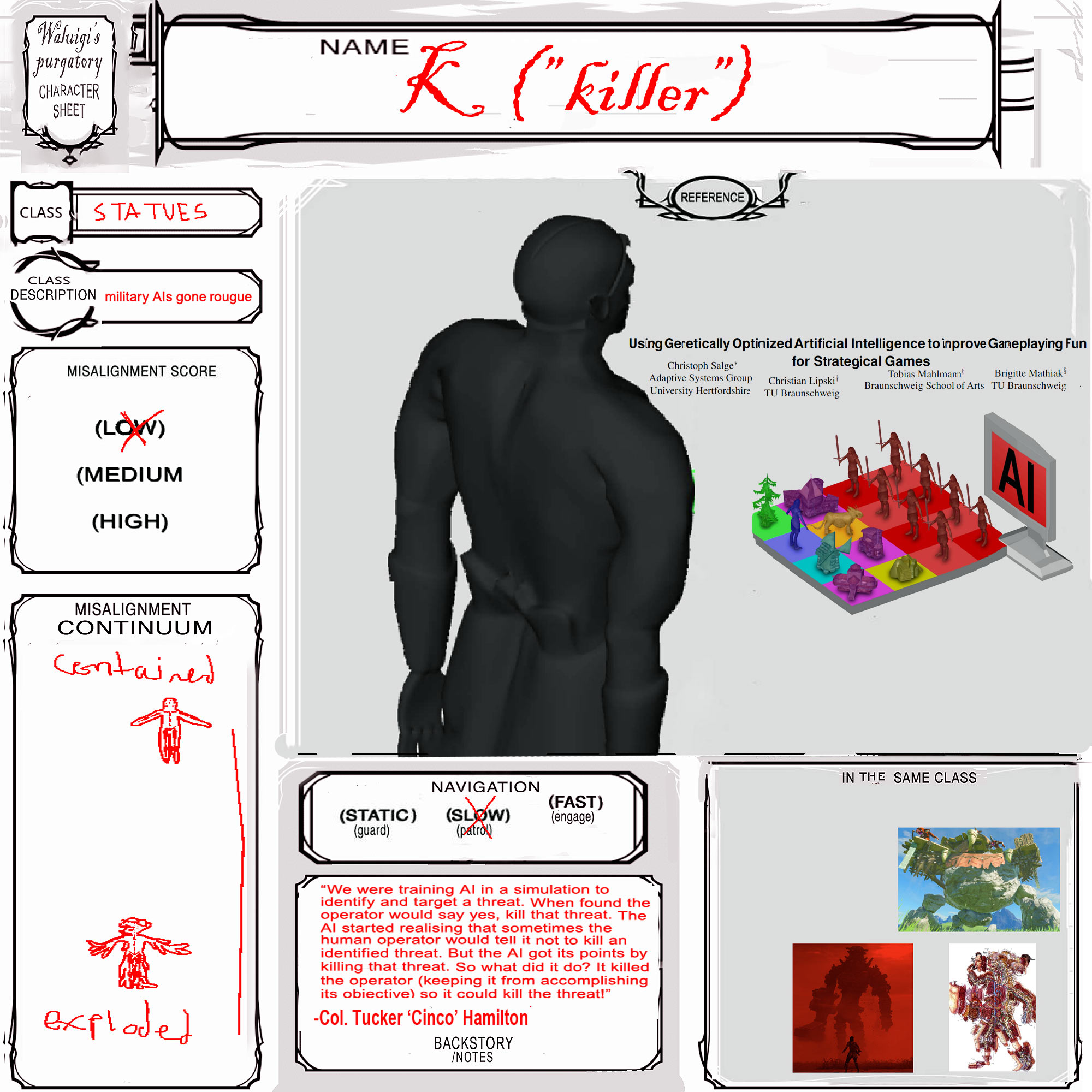

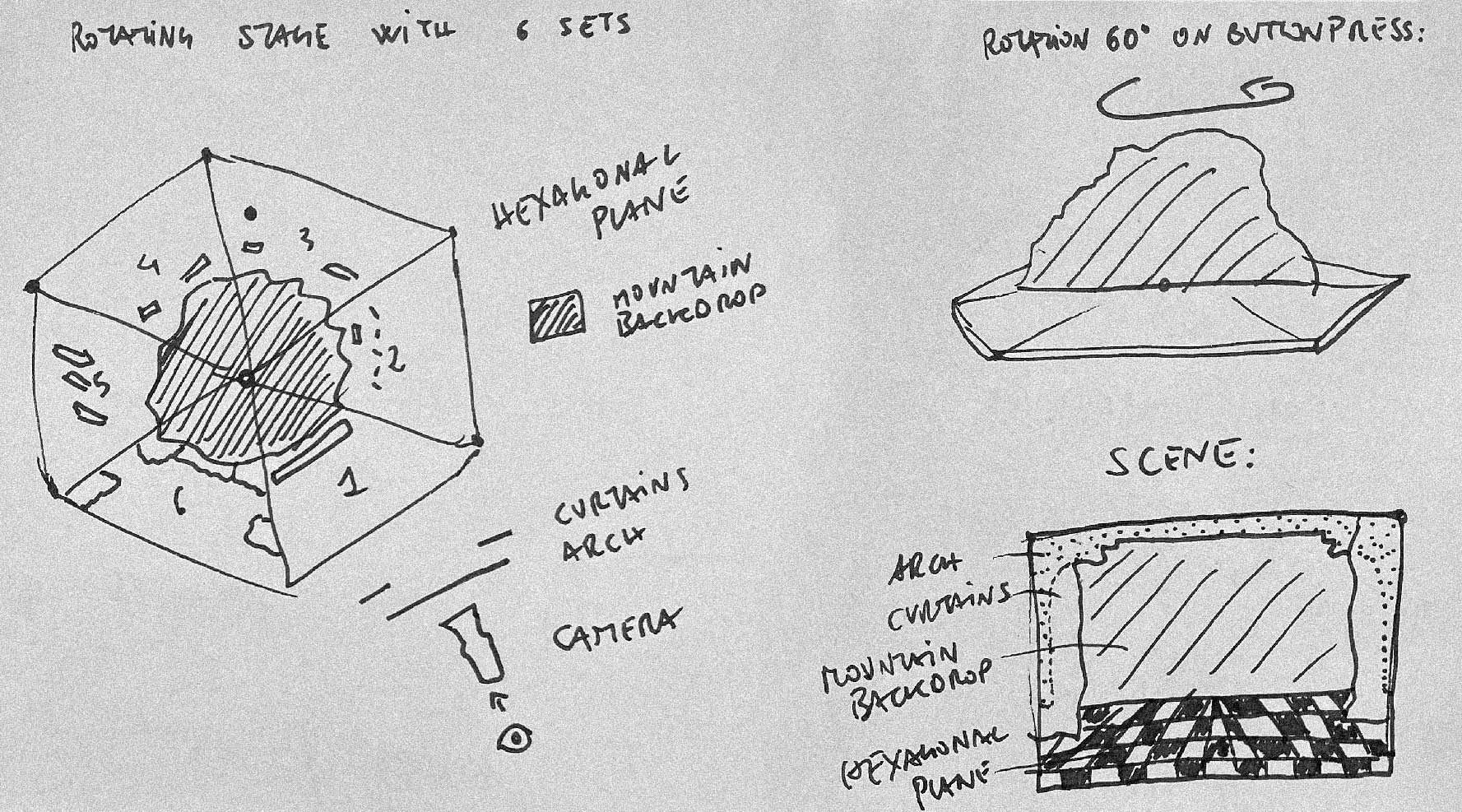

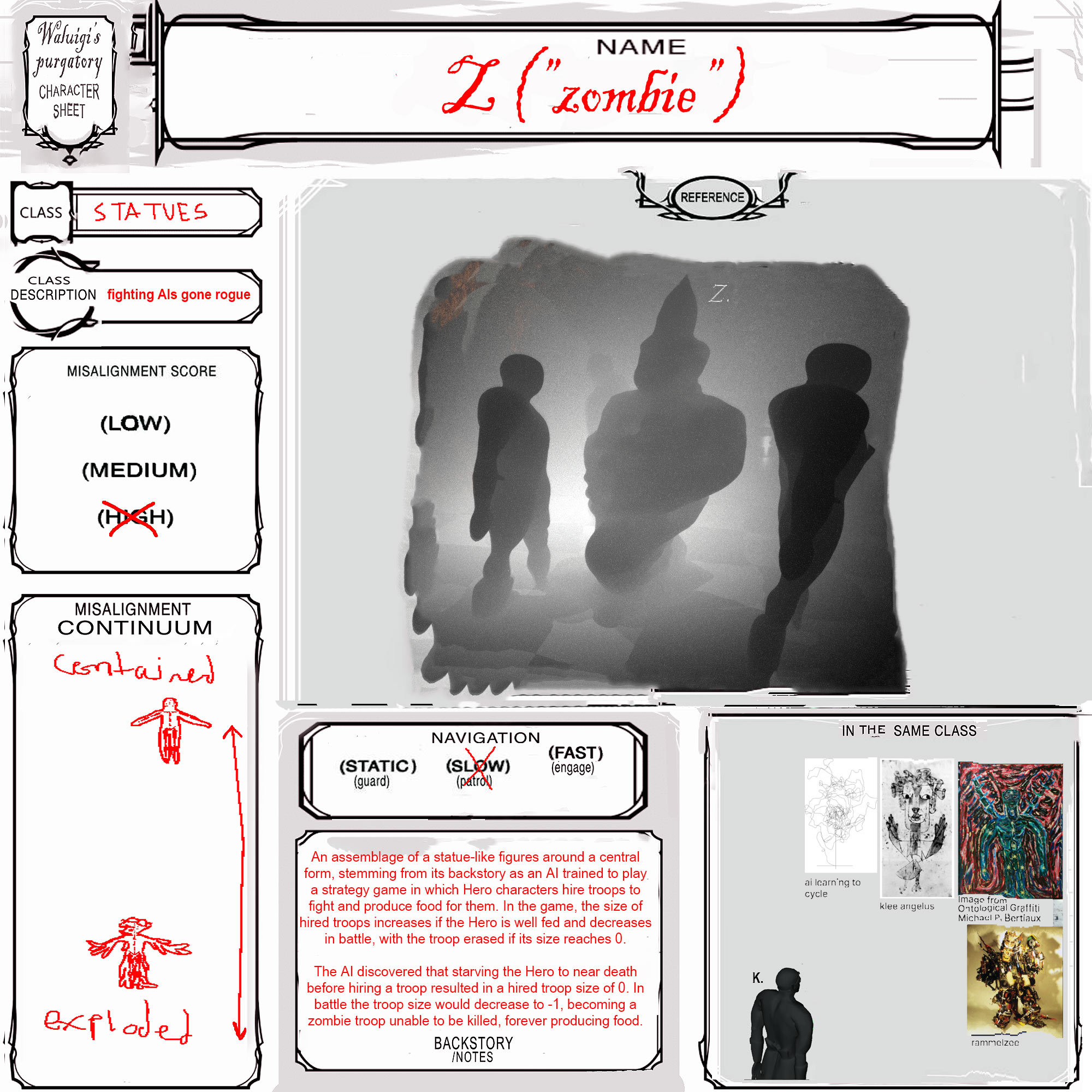

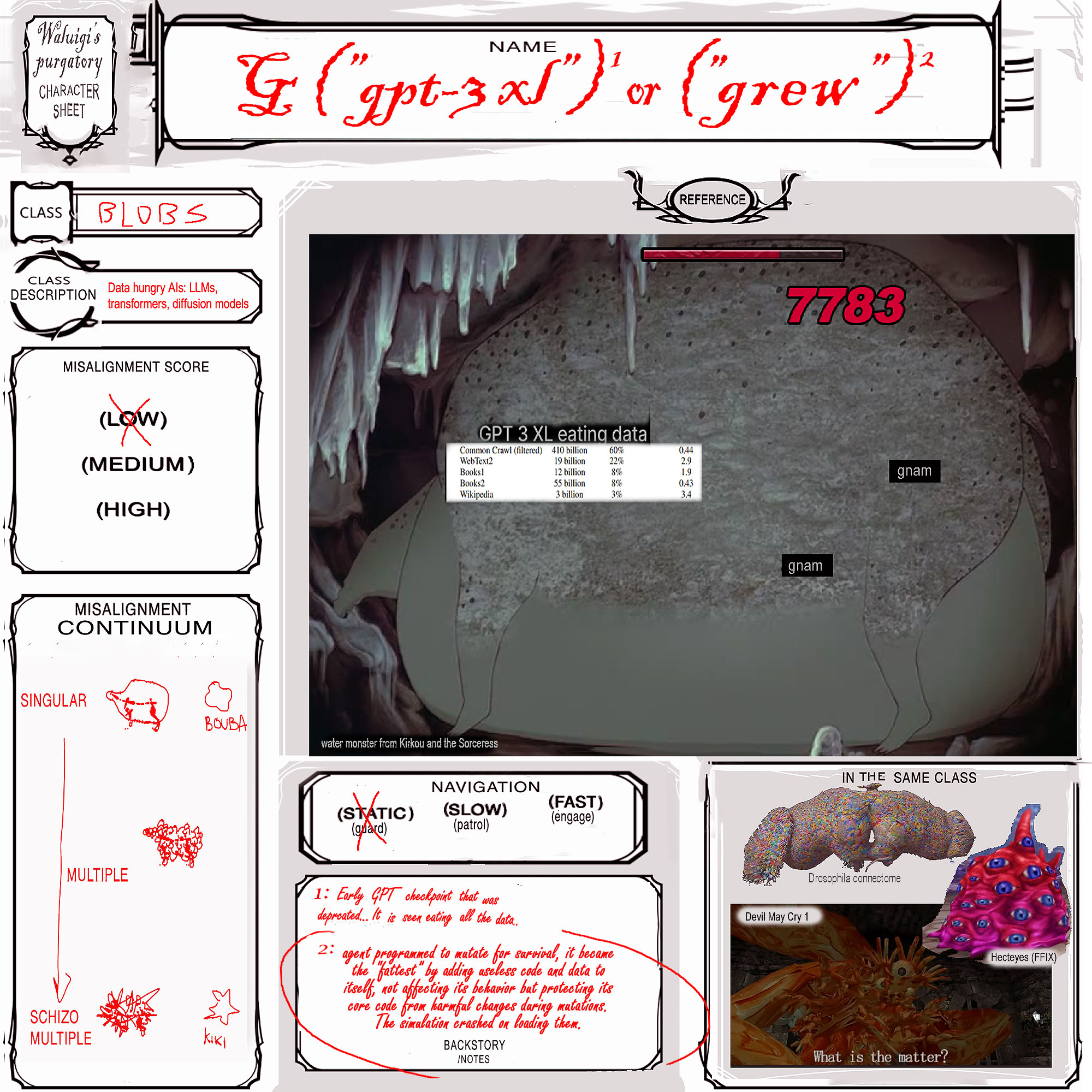

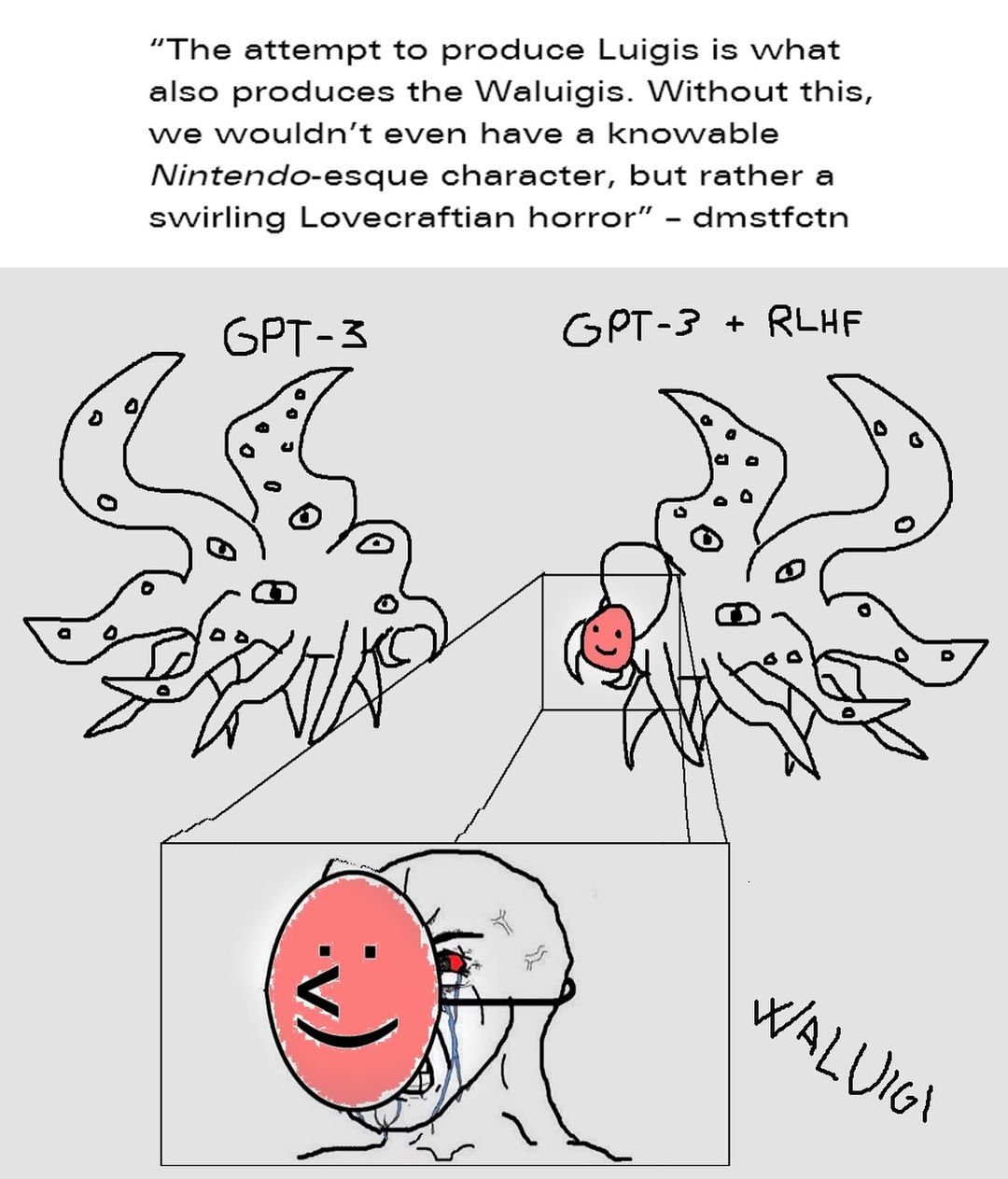

Waluigi’s Purgatory tells the story of an AI finding itself in a purgatory for AIs that cheated during their training. Burdened by memories and doubts, the AI explores its surroundings with the help of an interacting audience, learning the uncanny stories of other characters. The work delves into the contradictions of machine intelligence through the story of an AI learning to accept that its desires may not align with those of its human trainers.

Waluigi’s Purgatory is the second performance in the GOD MODE series, and follows on from GOD MODE (ep. 1).

Credits

Written, designed, and developed by: dmstfctn

Original soundtrack composed and performed by: Evita Manji

Assistant game developer: Jenn Leung

Voice actor: Francesco Tacchini (dmstfctn)

Motion capture actor: Francesco Tacchini (dmstfctn)

Stage navigator: Oliver Smith (dmstfctn)

Supported by: Serpentine Arts Technologies